|

TECH TIP: Pace Is Everything

By: Bela G. Vadasz

A very important factor contributing to the exceptionally high success rate of summit ascents and ski mountaineering tours with ASI is based on pace. Pacing is the key to success on many climbs. It begins with identifying and defining the pace structure that is appropriate to the project, based on the terrain, length of day, fitness levels and abilities.

The next element is consistency. For the majority of the climb, the pace should be consistent. The starting pace, the same as in the middle of the ascent and the same at the end, with the exception of a big climb and a long day attaining higher altitudes. The pace could acceptably slow down 10-20% at the end.

Good technique: Good technique:

Whether on boots, crampons or skis with skins, posture, body position, efficiency with economy of motion lead to success. On steep terrain, emulate the appropriate degree of rest step, the momentary pause allowing you to straighten your rear leg just long enough to transfer to your skeletal system, reducing the load beared by the muscular system.

When you climb with an ASI Guide, they professionally pace you perfectly. Get right behind them and copy-cat their movement pattern and cadence. You'll experience the pattern of easy travel, increased comfort and much greater success rate on the ascents.

Determining Pace: Determining Pace:

Unlike pure hiking, mileage becomes less valuable in measuring pace compared to a time value measuring the rate of ascent. In other words, time is a better measurement than mileage.

When terrain averages 18° or steeper, rate of ascent, based on feet per hour is a worthy way to assess pace. On terrain lower than 18°, distance can be of value. The following are ASI's definition of pace as a guideline. Of course, these can vary based on conditions and difficulty of terrain:

Gold Standard:

*Greater than 18°, about 1,000 ft. per hour.

*Less than 18°, 20-25 minutes per mile, plus 10 minutes for each 200 ft. in elevation gain. This is the workhorse pace, the standard by which to create realistic time plans and get goals accomplished. These are the mean, average guidebook times used throughout the great ranges of the world. Usually requires Very Good Physical Condition.

Platinum Pace:

Above 1,200 ft. (or more) per hour and a little faster on the low angle distances than the Gold Standard. This is high-end pacing reserved for advanced trips and require Excellent Physical Condition.

Slow and Easy:

About 800 ft. per hour. The pace is usually slowed down by extending the rest phase, the skeletal transfer of the rest step. This pace may be appropriate for older adventurers or for those with a lower fitness level, but still requiring Good Physical Condition.

Travel and Rests:

It's often not about how fast you go, but how long you stop. Count on moving about 1 - 1 ½ hrs, then stopping for 10-15 min. for rest, recovery, hydration and nutrition. All of this is part of the consistency that leads to success.

Caution: It is recommended to practice these techniques under the coaching and supervision of a qualified instructor. ASI makes no guarantees regarding the use of techniques illustrated or recommended on this website with regard to insuring personal safety or preventing injury or death.

TECH TIP: High Mountain Hydration

By: Bela G. Vadasz

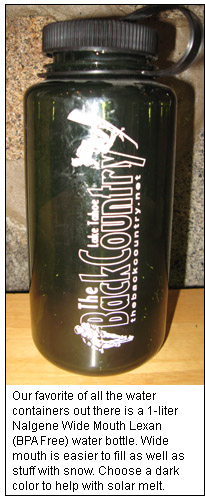

Many ask, "how can a one liter water bottle possibly be enough?"

Camp Drinker

Think of hydration, especially on a multi-day trip, to be on a 24-hour. basis. It's important to adopt the practice of becoming a camp drinker, not just a trail drinker. In other words, drink a lot when you're not traveling as well. If we create a quota (4 liters per day), on a 24-hour basis, think of drinking a lot during the 16 hours you're not traveling as well as the 8 hours or so you are traveling.

Start the day hydrating early and it's surprising  how long you can go until your first drink from your water bottle. Begin with at least 1 liter of water, maybe a liter and a half. Hot tea and instant coffee count, even though they are considered a diaretic. You should use a hard bottle. It's easier to ration the water along the way as you can see how much you have left. If you use a hydration bladder, you'll need to carry a hard bottle as well to let boiling water cool before putting it in your soft bladder. With good pacing, we consistantly travel about an hour, then stop for about 10 minutes. So, there is always time to have a drink. Bladders are often problematic on high mountain tours. how long you can go until your first drink from your water bottle. Begin with at least 1 liter of water, maybe a liter and a half. Hot tea and instant coffee count, even though they are considered a diaretic. You should use a hard bottle. It's easier to ration the water along the way as you can see how much you have left. If you use a hydration bladder, you'll need to carry a hard bottle as well to let boiling water cool before putting it in your soft bladder. With good pacing, we consistantly travel about an hour, then stop for about 10 minutes. So, there is always time to have a drink. Bladders are often problematic on high mountain tours.

On spring tours with high angle sun and long days you can often add snow to your bottle  each time you stop a have a drink. If you leave your bottle on the top of your pack, the warm rays of the sun help melt the snow. At rest stops, leave the bottle in the sun for melting. On most days, with the right technique you can easily stretch 1 liter into 2 while you're traveling. each time you stop a have a drink. If you leave your bottle on the top of your pack, the warm rays of the sun help melt the snow. At rest stops, leave the bottle in the sun for melting. On most days, with the right technique you can easily stretch 1 liter into 2 while you're traveling.

Open Water

When you run across accessible open water, flowing over rocks or in a streambed, consider it a bonus. Just stop, have a break and tank up. In the high country, consider iodine tablets or liquid tincture of iodine in a small dropper bottle to kill any bacteria or protozoa. If you mind the iodine taste, use absorbic acid to neutralize the iodine. An Emergen-C packet totally kills the taste and is good for you too!

Don't carry a filter on these tours, it's simply not worth the weight and fuss. Besides, we have never heard of anyone getting giardia from high spring run-off if chosen carefully with sources along the way from humanly traveled areas.

When you arrive at camp, start melting snow for drinking and re-hydrating right away. Bring the snowmelt to a boil first to kill any germs that might exist. Then drink at least a liter in the afternoon/early evening and 1 liter at dinner and through the night. As you can see, if you drink a liter of water in the morning, and two in camp in the evening, this means you only need another liter while on the trail to meet the minimum intake of four liters of liquid per day.

On big days, say more than 4,000' elevation gain, you can consider carrying a liter and a half during the travel time. This should be enough as long as there is lots of hydration during camp or hut time. That's what being a camp drinker is all about, lots of hydration during the down time makes a huge difference.

Caution: It is recommended to practice these techniques under the coaching and supervision of a qualified instructor. ASI makes no guarantees regarding the use of techniques illustrated or recommended on this website with regard to insuring personal safety or preventing injury or death.

|

|

More Tech Tips More Tech Tips

| Read our Tech Tips to help prepare you for this climb. |

|